Does Advertising Ruin Everything?

“We have to get over our addiction to free stuff. Suck it up and pay,” says Tim Wu, the author of a new book on the history of ads.

Harvesting was perhaps the original U.S. industrial activity. Economic growth relied on the reliable conversion of plants and animals into salable products, like cotton and beef. But the 21st century’s most successful industrialists, like Facebook and Google, harvest another commodity as abundant as wheat or crude oil. In the new industry, the fields are media and entertainment, the harvesters are advertisers, and the crop is attention.

In his new book, The Attention Merchants, the Columbia University professor and writer Tim Wu traces the history of the advertising business from its origins in the 19th century to the modern phenomenon of ad-blocking software on websites. Wu is widely known for his previous book The Master Switch, a history of media companies, and his coining of the term “net neutrality.” We spoke earlier this week about advertising as the modern iteration of religious evangelism and the effect of advertising on journalism and television. This transcript has been edited for concision and clarity.

Derek Thompson: An important part of attention is focus, so let’s zoom all the way in. What is this book’s thesis?

Tim Wu: The descriptive thesis is that there is a strange business model called advertising-supported media that was once restricted to a small area of our life, like newspapers, but now it is taking over every area of our life. I wanted to understand the history of advertising, because it didn’t simply always exist this way. You typically would just pay for stuff, like newspapers or movies. The idea of selling a captive audience had to be invented.

And the normative question is: What are the costs of everything being free? Are we paying in other ways? There is a covenant that, in exchange for free stuff, we expose ourselves to advertising. But is that covenant broken?

Thompson: The idea that advertising is a strange idea is, frankly, a strange idea. I unlock my phone, and I’m swimming in ads. I walk outside: ads. I turn on the television: more ads. The first popular radio news programs were in the early 20th century, so literally nobody alive today can recall a period where they were not being constantly bombarded by commercial messages.

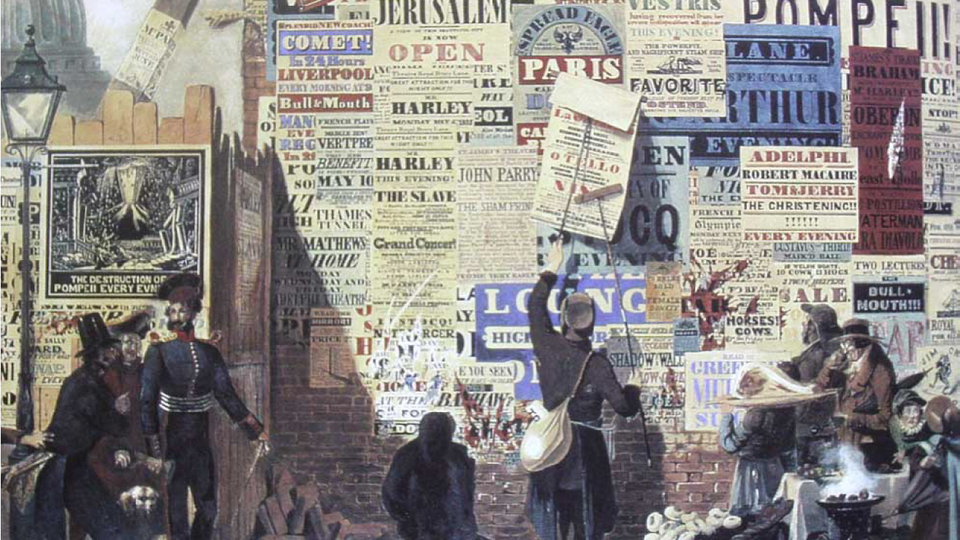

Wu: I think that most people think there has always been advertising, that it is a fact of nature. But modern advertising had to be invented. Somebody had to develop the techniques of getting people’s attention and then driving them to a product they wouldn’t otherwise want.

The history of advertising is not well known. Many of the early ad men specialized in selling medicine. Many were former preachers or related to preachers. In the 19th century, advertising drew from traditions of religious propaganda, and the idea that our advertising culture draws from religious practice is fascinating to me.

Thompson: You trace the origins of advertising to the story of an 1830s newspaper man named Benjamin Day. What was his genius?

Wu: Newspapers were once a sleepy business. They often sold for a relatively high price. Then in the 1830s, this fellow Benjamin Day, his paper was the New York Sun, and he was perhaps the first true attention merchant. Day had a brilliant idea to dramatically reduce the price, amass a large readership, and convert his customers into a product, which he could sell to an advertiser. This insight spread across media to become the dominant form of selling the news.

His story shows both the promise and the ethical challenges inherent to the advertising business model. Because once your goal is to gather the largest audience possible, that puts you in a race toward the more lurid, spectacular, and attention-getting media. Day’s paper included lots of violence crime and death, but it also very quickly got into fabricating stories.

Thompson: I can imagine some readers drawing a straight line from Day’s sensational 1830s papers to online clickbait today, concluding that advertising encourages a race to the bottom to maximize attention on a per-unit basis. But it’s also the case that advertising democratizes news and information, making freely available to the many that which used to be open only to the rich. And that sort of business model is good because it pays for more reporters and journalism.

Wu: I think it’s all there in the story of Benjamin Day. The potential and the risk of advertising. To Day's credit, he brought the news to everybody. Newspapers were a very elite product before the opening of the penny press. There is a democratizing element to advertising that makes these products cheap and available to the masses. That is is good. But it should be done very, very carefully. A business model that relies above all else on attention is always prone to the sensational.

Thompson: What is the most controversial idea in the book?

Wu: A subtle thesis of the book is that business overtook religion in the 20th century. For most of human existence, who told you what to think? Preachers did. Religion did. But I think that, through advertising, business has displaced religion as the primary instructor of human deliverance.

I tell the story of Claude Hopkins, who is famed as one of the inventors of modern advertising. He was a funny guy with a lisp, and he was socially awkward. He was a baptist preacher as a teenager, who quit and took his talent to copywriting and virtually invented the idea of the copy writer as a genius in the early 20th century. He invented the Don Draper figure. His strategy was very closely related to the protestant-preacher style of deliverance. He imported ideas of religious conversion directly into the advertising world. His autobiography, My Life in Advertising, is full of falsehoods. You can't decide if he was one of the most evil people of the 20th century or a lovable genius.

Thompson: Right now, we’re at an interesting inflection point in ad-supported media. On the one hand, you have Facebook and Google, two enormous ad-based companies that are collectively worth about $900 billion. On the other hand, you have structural decline in the broadcast-television business as more young people watch subscription television, like Netflix and HBO Now, where there are no commercials. So audiences, and especially young people, are simultaneously running away from advertising on television while running toward it on their phones. Is this a golden age for advertising? Or the beginning of an Ice Age? Or an unstable and unsure moment?

Wu: We are in a moment of revolt against major forms of advertising. You can see it in the decline in NFL ratings, the abandonment of traditional television. But some things are growing that are ad-based. Revolutions are confusing in real time. They’re often only clear in retrospect.

I would say that heavy advertising load hasn’t arrived at some of the social media yet. Snapchat and Twitter are still in their relatively early days, and the full load hasn’t arrived, unlike the barrage of ads you see in the fourth quarter of a football game. There is always this delay factor. Young people will always be running to these apps before they add advertising. YouTube got people hooked before they turned up the ad load. But you look at YouTube now, and I think the terms have gone beyond TV, where it feels like a third of the time spent on YouTube is watching ads. That is why there is this move among people who cannot stand advertising and are going to Netflix and Amazon Video.

Thompson: Yours is a testable hypothesis. If investors are reading this interview, they might say, “Tim Wu is seeing a cultural shift against ads that spells the long-term demise of ad-sponsored businesses.” Then they would place a huge bet on an ad-free media portfolio, including Netflix and Amazon and against Facebook and BuzzFeed. But how would websites survive that future? How would The Atlantic survive?

Wu: I have a personal theory about traditional media, like newspaper and magazine sites, which is that they are crazy to go it alone and try to build their own little army. They should be more focused on getting readers to subscribe to a one-pass for everything that’s worth reading before Facebook essentially does this for them.

Thompson: For example, you’re talking about a hypothetical product where readers could subscribe to The Atlantic, The New Yorker, the New York Times all at once with a discounted price and have special access to those print products and sites.

Wu: Right. Something like that.

Thompson: The whole idea that news should cost money has been a casualty of the Internet and the new abundance of free—or, ad-supported—sites. If The Atlantic puts up a wall, maybe readers will just go somewhere else.

Wu: Yes, and that’s why a part of my message is to consumers. We have to get over our addiction to free stuff. Suck it up and pay. A lot of people say, “I hate ads, I’m sick of ads, I’m sick of clickbait, I’m sick of this race to the bottom.” If you say that, you have to put your money where your mouth is. We have to get over our addiction to free if we’re going to save the web. That’s us, the users. We can’t expect everything to be free and to be good.

Thompson: Unlike cable television, which is very expensive but also very good.

Wu: The history of the last 10 years of the Web is a bit like the first 10 years of television. There were all these great hopes for what TV would be. But then it became an ad battle, and the only programs that succeeded were game shows and cowboys. Television only got better with the rise of paywalls [like premium cable].

Thompson: What if game shows and cowboys succeeded because people like game shows and cowboys? Perhaps the ultimate culprit here is that large audiences might have worse taste than you or I would prefer.

Wu: I realize that not everybody has the same taste as me. But if you go through American media history, you see that there are times when the programs clearly get better and where the offerings are more diverse. There have always been shows that no critics liked. But television has been terrific over the the last 10 years, and I think that the economic structure of premium cable and subscription television has been an enormous factor.

Thompson: One irony of the superabundance of advertising on the Internet and on our phones is that, per the principle of inflation, there is so much competition that each individual advertisement is worth less. I wonder whether advertising itself is in a race to the bottom on the Web. It’s impossible to predict the future of anything, but what’s a smart way to think about the future of advertising and media?

Wu: The attention-merchant business model is in constant need of growth, and the way it has grown historically is either to find new times and space where we’re not occupied or to more subtly exploit the time that is already there. That suggests that all the periods you now regard as refuges or escapes from your crazy life will inevitably become targeted, because that’s where the growth activities are. For example, there has been a move to bring more ads to national parks, inside public schools, and into other sanctuaries that were previously walled off. As people are harder to reach, the efforts to advertise to them became more disguised, more intrusive, and more manipulative.

If I were in charge of the universe, I would say we need a new covenant—a new deal between advertisers and consumers, to make some times and places off limits. Where we want to be is where many print magazines are right now. The ads are beautiful and often very interesting, but looking at them doesn't ruin the magazine. That would be peace in our time.